If I Can Do It

The Story of One Woman’s Rise from Poverty

When I was small, my mother chose her new man over me—and put me out.

As a child without a home, my grandmother reluctantly took me in.

As a girl, my aunts bullied me into doing their chores.

When I was a teen, I searched for bottles to return for pennies.

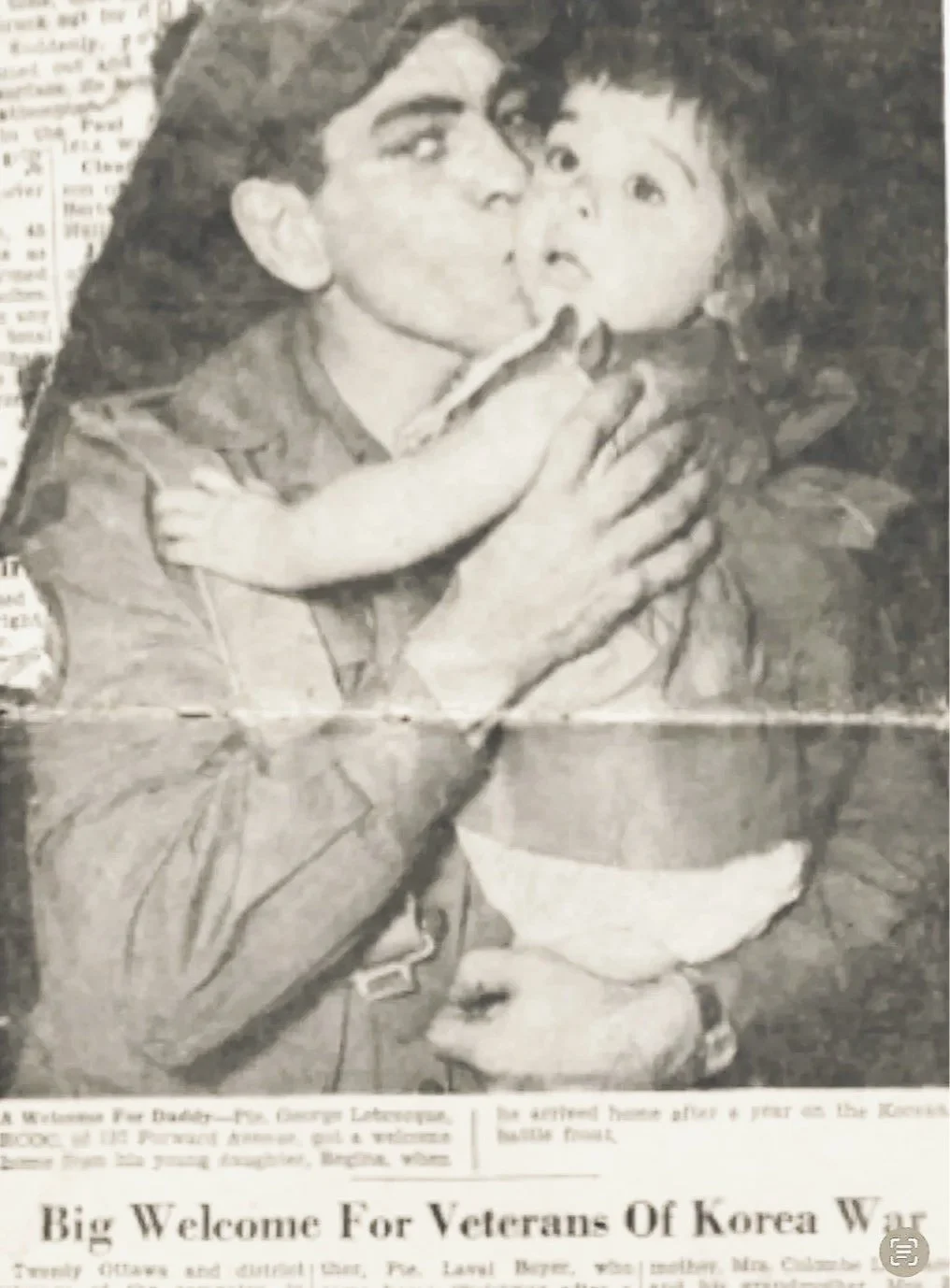

As a woman, a man approached me and said, “Manon, I’m your father.”

The life of Manon de Villiers is much more than a rags-to-riches tale—it’s a singular story of perseverance and self-belief.

In Her Own Words

If poor kids seem to enjoy sunshine more than rich ones, it’s because it’s free. I know this because as a child, no matter where I went or what I did poverty was there, trying to bully me. When I pulled myself from my crowded bed, it tried to hold me down. When I dragged my chair to the table, it was reluctant to feed me. When I tried to sleep, it didn’t care that I was cold.

Coming to my rescue was not Prince Charming but a funny, loving, grey-haired man. At six foot three, my grandfather was a friendly giant who gave me strength and taught me to work as hard as he. Not that he had a choice. His monthly pay of a hundred dollars had to provide for the eight people who lived in his little house.

The place I came from was called poverty but it was a birthright that I chose not to make my destiny. I escaped its long shadow with hard work and determination. If by chance you come from the same place, I know that you too can escape it, just as I did.

Why did Manon choose an e-book?

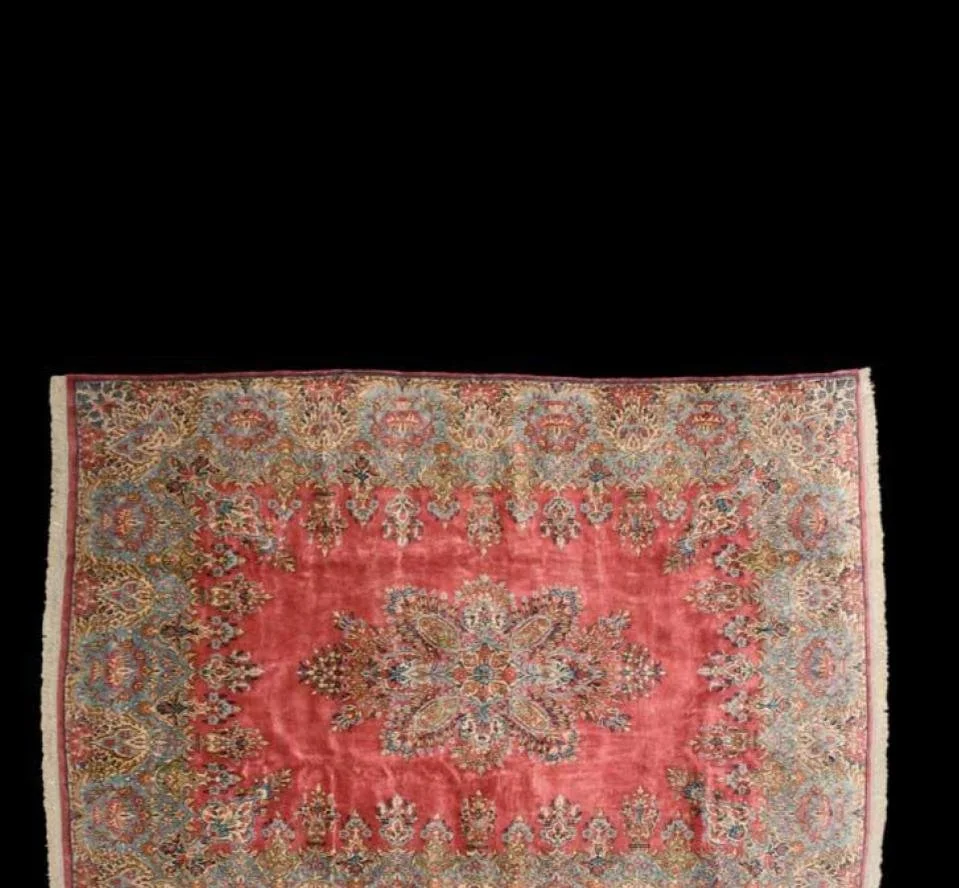

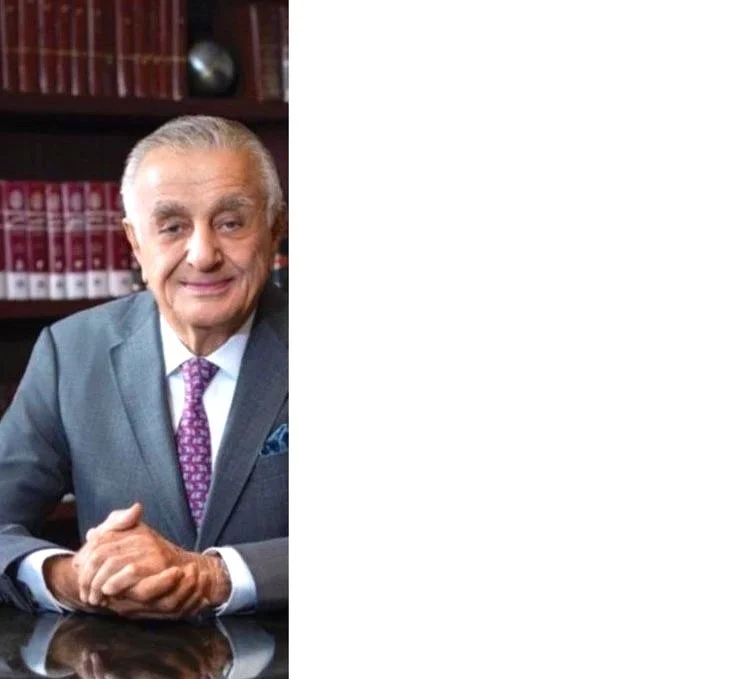

Mohammad’s great-grandfather was a man of consequence in 19th century Persia. Of Grand Ayatollah Haj Agha Mohsen Araki, Mohammad writes:

“Rather than heed the advice of the prime minister who suggested he reduce his six-horse carriage to four to match that of the Shah (lest the Shah become jealous), he suggested instead that the Shah should add two horses to his own!”

Grand Ayatollah Haj Agha Mohsen dominated the carpet trade across the central Iranian plateau from the mid-1800s onward. Persian carpets woven in his villages were notable for their exceptional beauty and durability. To this day, many remain fixtures in Europe’s most distinguished homes.

Mohammad enjoyed the fun-filled life of a typical schoolboy in mid-20th century Iran. Of a coat his mother had given him, pictured on the left, he writes:

“When I was eleven, my mother gave me a wool jacket that I adored so much that I refused to take it off—even in the blazing summer heat when the mercury climbed to forty degrees. Looking back, I must have been quite a sight, grinning proudly while slowly roasting in my beloved coat!”

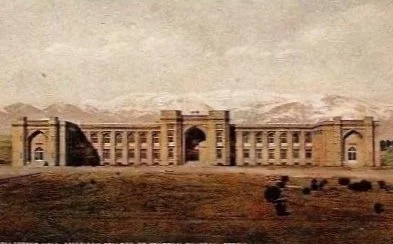

As a teenager, Mohammad left Sultanabad—by then renamed Arak—for the renowned American School of Tehran, one of the Middle East’s first Western-style high schools, founded in 1873. It has been alma mater to many of Iran’s prominent businessmen, politicians, and captains of industry.

As a young man, Mohammad traveled first to Europe, then to Britain, where he and his cousins studied in Bournemouth before earning admission to some of London’s finest universities. Reflecting on their time along the English coast, he writes:

“All of us cousins were thrilled to be by the water, and we went down to the beach as often as we could. Even though the south of England is notorious for rain and fog, we were in our late teens, and nothing could dampen our spirits.”

Upon graduation, Mohammad returned to Iran and began a remarkable 15-year career overseeing major infrastructure projects for the government of Iran’s last Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Mohammad’s career in Iran came to an end with the fall of the monarchy and the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979. Amid fierce fighting in the country's major cities, the Shah was forced into exile—never to return. Of the dangers, Mohammad writes:

“I walked the streets of Tehran in shock. The Shah’s security forces were firing on protesters, and fighting erupted everywhere I turned. More than once, I froze on the sidewalk, praying I wouldn’t be noticed by government troops as they exchanged gunfire with protesters who refused to back down.”

Mohammad moved his family to safety in England in 1979.

After completing the executive program at Oxford University in London, he emigrated to Canada and made Vancouver’s Point Grey the new home for himself and his family.

“In addition to Vancouver's mountains, a major attraction was the city’s access to open water, with its safe beaches and opportunities for saltwater swimming. Unlike the Thames, which is salty but not suitable for swimming, Vancouver’s beaches are perfect for a swim, even for dogs!”

The Mohsenis have enjoyed many fun and fascinating family vacations over the years.

Mohammad’s achievements in business have enabled him to devote himself to philanthropy, turning his personal success into a story of compassion and generousity.

“The Churchillian quote that holds the most significance for me is, "We make a living by what we get. We make a life by what we give.””

The Mohseni Foundation supports health and education initiatives in communities throughout British Columbia and central Iran.